scar stories

students share history behind marks on their skin

Self Harm

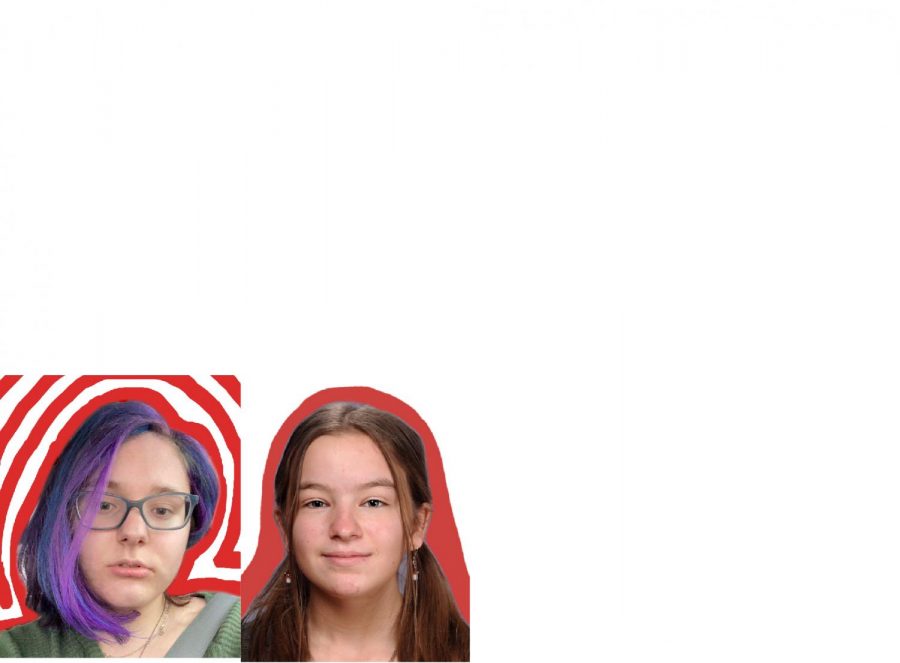

After learning about it from a source that glamorized it, junior Liz McIntrye began a five-year battle with self-harm.

“[I started in] sixth grade,” McIntrye said. “I stopped in eighth grade, but then I picked it back up in ninth grade.”

McIntrye has mixed feelings about the scars on her arms and upper thighs. On one hand, they show her strength. On the other hand, they sometimes evoke negative emotions.

“It symbolizes that I’m a fighter and a survivor,” McIntyre said. “I’d say I’m ashamed because I did it to myself and not a lot of people go through that.”

McIntryre hides her scars depending on the situation she’s in.

“If I’m going to something more professional, I’ll probably wear long sleeves,” McIntyre said. “If I’m going to something like a friend’s house, then I’ll wear something [short-sleeved].

When people see McIntrye’s scars and hear of the history behind them, they’re typically worried.

“They were scared and confused because they don’t understand what I’m going through,” McIntyre said.

McIntyre believes society in general has a misconception about people who self-harm and their reasons for hurting themselves.

“Society is a big mess in general, but they treat it as being selfish, which it’s not,” McIntyre said. “We don’t see how we affect other people when we do this, so they call it selfish. We’re so caught up in our own emotions.”

On the internet especially, many people make jokes about self-harms, such as comparing self-harm scars to barcodes.

“If [the joke] was directed toward me, I’d probably get angry,” McIntrye said. “[They] have no right to assume anything about me.

People make self-harm jokes for different reasons.

“The people that self-harm do it to cope,” McIntyre said. “The people that don’t [are] just trying to be funny. They’re ignorant.”

McIntyre advises those who aren’t sympathetic to the topic to be more informed.

“Educate yourself on things you don’t know about or things you’re scared of because that’ll make things easier for everyone else,” she said.

She believes that showing self-harm from a negative perspective and hiding sharp objects can help stop it from happening.

“Knowledge is key, so I wouldn’t want [children] figuring out about [self-harm] by themselves,” McIntyre said. “It is dangerous, but if they hear from the right person, they might not do it.”

To those who struggle with the same issue, McIntyre said to look at their scars optimistically.

“[Don’t] flaunt them, but embrace them,” McIntyre said. “Self-harm is not a sign of weakness. You’re a survivor because you’re still here. That makes you strong, so don’t hate yourself.”

Surgery

After multiple minor surgeries, junior Sofia Hughes was left with scars.

“I was born with club feet, which basically means my feet were inverted inward,” Hughes said.

The condition, which affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. each year, is genetic.

“It was passed down to me on both sides of my family,” Hughes said. “My dad has it. My second cousin twice removed or something has it.”

Hughes had the surgical procedures in elementary and middle school, which resulted in two sets of scars on her feet.

“When I was a baby, I had all of these corrective casts and surgeries just to put my feet back into the right position so I can walk,” Hughes said. “That worked for a long time, and then in second grade one of my feet started turning inward, so I had to have what was called a tendon transfer to make my foot pull outward again. They took a tendon that was pulling my foot inward and they moved it further to the outside of my foot. I had that done on my left foot in second grade and my right foot in sixth grade.“

Hughes used to place more value on her scars.

“I used to be more proud of it,” Hughes said. “There was a time in second or sixth grade when that was one of the worst things that I had to go through because surgery is scary. Now it’s so far in the past that it’s not much of a testament to who I am now.”

People usually react to Hughes’ scars with worry and wonder.

“[They’re] like, ‘Oh, what’s that? Are you OK?’” Hughes said. “They’re either concerned or curious. Sometimes [they’re] sympathetic.”

Hughes has become unfazed by most reactions to her scars.

“I don’t really care what other people’s reactions are,” Hughes said. “If it’s anything out of the ordinary, I’ll just be amused.”

Although the last surgery was five years ago, there are lingering effects of Hughes’ surgeries.

“My feet and ankles get messed up pretty easily,” Hughes said. “There was a point during quarantine where I stepped wrong, and I used crutches for a week just so I wouldn’t mess up my feet further. I have to be really careful. I wear inserts in my shoes just cause I need the support. I can’t wear high heels, which sucks cause I’m so short that I need it.”

Although Hughes now feels comfortable with her scars, she recognizes others may reasonably have differing opinions about their own scars.

“However you feel about your scars is OK and valid,” Hughes said. “You’re allowed to be proud of them because it means you survived something that wasn’t easy. Don’t let anyone tell you how you’re supposed to feel about it because it’s your body. It’s your experience.”

Stephanie Kontopanos is a senior and the assistant editor of The Tiger Print. This is her third year on staff and her second year being the Newspaper Grandma...