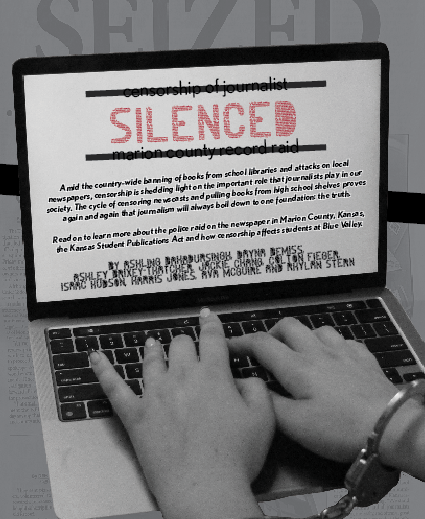

Amid the country-wide banning of books from school libraries and attacks on local newspapers, censorship is shedding light on the important role that journalists play in our society. The cycle of censoring newscasts and pulling books from high school shelves proves again and again that journalism will always boil down to one foundation: the truth. Read on to learn more about the police raid on the newspaper in Marion County, Kansas, the Kansas Student Publications Act and how censorship affects students at Blue Valley.

Marion County Details

On Aug. 11, Marion County, KS police raided the local newspaper’s office and took belongings such as computers, phones and hard drives to use as evidence for a supposed DUI case.

The raid, led by Marion Country Police chief, Gideon Cody, formerly the chief of the KCMO police, was trying to illegally investigate the computer of one of the Marion County Record’s reporters.

The police also raided the home of the co-owners of the paper, 98-year-old Joan Meyer, who passed away from sudden cardiac arrest the next day, and her son, Eric Meyer, who has since spoken out about the attack on his publication, saying, “We can’t allow police to come running through newsrooms and seizing things.”

A reporter for the Marion County Record allegedly lied to gain access to a restaurant owner’s driving records, so the Sheriff’s department created electronic copies of private Marion County Record files belonging to the newspaper.

Days later, a county attorney proclaimed there was not enough evidence to show just cause for the raid, and the police were given a court order to return the confiscated items, which they did but also kept an electronic copy of the files they secretly made.

“An attack on a newspaper office through an illegal search is not just an infringement on the rights of journalists but an assault on the very foundation of democracy and the public’s right to know,” said Emily Bradbury, executive director of the Kansas Press Association.

Not just a paper

Carol Williamson, a citizen in Marion County, shares her personal experience with the issue. Williamson is the grandmother of freshman Cady Reynolds.

“My grandma was really passionate about stuff like that,” Reynolds said. “She texted me and then I also saw it in the in headlines. I didn’t really know what it was until she like kind of exploded it.”

Once she found out about the raid, Williamson knew she needed to do something since feels a personal connection to the town and the Marion County Record, having been raised there.

Living in a small town, the newspaper is important. It not only shares news to bring the community together, but it also gives a small town a closer feel.

Regardless of how someone feels about a particular topic, Reynolds said the freedom of the press shouldn’t be taken away.

“I understand why you might not want to [cover particular topics] because they’re either very controversial or they would cause a riff in the student body,” Reynolds said. “If you start talking politics a lot — I understand why that’s something that you would stray away from, but generally [everything’s] all OK.”

After the raid, the community of Marion knew they needed to help; this included Williamson. Shortly thereafter, she started volunteering at the small organization.

“News serves an important purpose in our society,” Williamson said. “If there’s someone in government or higher power that is either abusing their power or neglecting their duties, it causes issues for everyone. I think that’s one of their responsibilities — to celebrate the community and to help people be better connected.”

By supporting your small town newspaper, citizens not only help the paper grow, but they help build a better community.

Williamson said the Marion County Record is not just a publication, it is a place of community for the residents.

“The stories tie people together,” Williamson said. “It’s not just about who won the football game and the honor roll of the kids in high school. It’s about sharing news in the community and knowing what’s going on in the world.”

The Kansas Student Publication Act states that:

The liberty of the press in student publications shall be protected. School employees may regulate the number, length, frequency, distribution and format of student publications. Material shall not be suppressed solely because it involves political or controversial subject matter. Review of material prepared for student publications and encouragement of the expression of such material in a manner that is consistent with high standards of English and journalism shall not be deemed to be or construed as a restraint on publication of the material or an abridgment of the right to freedom of expression in student publications.

Just a minutes away

Some high school news publications are censored by their school’s administration, which means that articles have to go through a screening in order to be published. Students’ work can be deleted for the information in it or the story it told.

As a result of several censorship disputes in surrounding states, such as the Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier Supreme Court case, the Kansas Student Publication Act was put into effect in 1992. The Act protects the right to free press for students at public high schools and is one of the strongest open record laws in the United States.

“Students have the right to publish even ‘controversial’ content in their school publications, according to the law,” according to the website of the Kansas Scholastic Press Association.

Being allowed to publish raw and true stories, students are also civilly responsible for their work.

Kansans have had this publication protection since 1992, but in just a few minutes’ drive away, Missouri is hopeful for the freedom that might come with the Cronkite New Voices Act. The New Voices Act is similar to Kansas’s but still allows administrators to deem a topic too controversial.

The pending Missouri Act states that “[school districts] may also restrict speech that is offensive or threatening.”

In response to the act, Missouri high schools have relaxed their grip. In St. Louis especially, schools have found a way to practice true journalism.

“Some school districts around St. Louis have passed their own rules prohibiting school officials from conducting prior review,” according to the St. Louis Public Radio, a division of NPR.

A journalism student at Clayton High School in St. Louis, senior Rachel Chung spoke on how her school manages their freedom of expression.

“Our newspaper doesn’t go through any members of the administration, the principal or anybody,” she said. “It’s funded by members of the community and it’s not funded by the school. [We] make sure to not have any ties to the school, and in doing so we don’t have too many censorship [restrictions].”

Clayton’s newspaper class is considered a zero-hour, where it almost acts like a club, and the students meet before school. This may be due to the fact that the publication cannot have any ties to the school. Although their newspaper tries to run separately, the office also tries to moderate what is being published.

“Recently we tried to do a story about Wi-Fi but the administration tried to be like ‘Hey, you can’t say this sort of stuff about how restrictive the Wi-Fi is,'” Chung said. “We just published it anyway.”

Students in Kansas are fortunate to be protected by the Kansas Student Publication Act.

Here at Blue Valley, students in journalism have the freedom to share their voices on topics they care about. They have the freedom to determine the content in the issue and learn the impact raw journalism can have.

Seized but never silenced

In light of the recent raid on the Marion County Record, discussions of censorship in the news and media have picked up. Junior Ava Aslinia, senior Mackenzie Franco, and KSPA’s executive director Eric Thomas shared their thoughts on the raid and censorship as a whole.

“My first reaction was just shock because you just don’t hear about these kinds of incursions against professional newspapers in the United States,” Thomas said.

Aslinia felt similarly about the subject.

“Journalism is a chance for people to express their ideas,” Aslinia said. “It’s important to be able to have free press because that’s where ideas can most easily be written out and spread so people can kind of hear those different perspectives.”

Franko, one of the editors-in-chief of BV’s yearbook, also had insight to share.

“Censorship limits some people’s knowledge of information,” she said, “If it’s not getting written about or posted, then they aren’t going to know about it.”

Within the past several years, the First Amendment has been continuously brought up in the news as free speech rights continue to be infringed upon.

“It almost feels like a history lesson when we’re talking about the foundations of free speech — so much of what we take for granted as American rights are have been established since the 17th or 18th century,” Thomas said. “The founding fathers [wrote] the ideas of freedom of speech, [but] those ideas are so old that we don’t even have pictures of the people who came up with [them].”

These kinds of attacks on free speech affect citizens of all ages.

“People from the age of 15 to 25 are encountering a totally different landscape than what the generation before it encountered,” Thomas said. “It’s probably is different from most any generation since the 1960s,

The consensus between Franko, Thomas and Aslinia was that journalism is about truth.

“You should go at it in a neutral position and try to present the facts as best as you can,” Franko said. “I don’t think any [topic] should be off limits.”

Censorship acts as a severe detriment to the people of this nation and students alike.

“It decimates our ability to debate with one another and exchange ideas we don’t agree with,” Aslinia said. “If we just don’t listen to anything we disagree with, then we don’t know how to defend what we believe is true.”