Masterpiece or Malarkey?

“My 5-year-old could have done that.”

“It’s just a bunch of squares.”

“It looks like scribbles.”

These are the common things internet “critics” have to say about modern art.

Modern art, as defined by the director of the Art Genome Project Jessica Backus, is art from the 1900s to the present day. This includes works by famous artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko, all of whom provide evidence as to why modern art is a legitimate expression of human creativity.

A common target of internet critics is Duchamp’s famous — or infamous — work “Fountain.” It depicts a urinal turned on its back with the inscription “R. Mutt 1917”.

A urinal? That’s right. How exactly is that art? It’s just a toilet with some graffiti on it. While that is true, the context with how pieces such as this come to be is essential to understanding modern art.

This piece was submitted by Duchamp to the newly established Society of Independent Artists in order to test the extent to which the society would follow their constitution, which stated they would accept any artwork submitted by their members as long as a fee was paid.

However, the work was rejected by the board of directors. In response to this act of censorship, Duchamp resigned from the society.

This was a big deal at the time since, according to TateModernArt.com, many had put faith in the idea of a “jury-free exhibition” in New York.

Duchamp’s act of shirking traditions and pushing boundaries revealed the hypocrisy of the art directors. This is trolling before the internet. While everyone else was in 1917, Duchamp was in 2017 s***posting before it was cool, or even existed. Duchamp’s purpose was to incite confusion and even anger. These intense negative reactions toward a urinal have persisted for literally over 100 years with hundreds of internet “cultural commentators” creating video after video as to why modern art is trash with Duchamp’s work consistently appearing as a centerpiece. If we understand art to be something that insights emotional reaction then why should Fountain not be considered such?

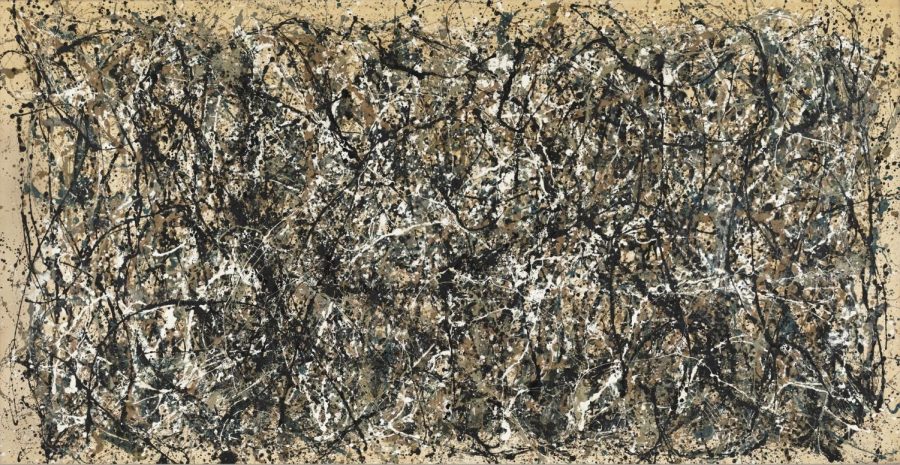

A common target for internet “art critics” is Jackson Pollock. He is commonly derided for producing “child-like” paintings that amount to nothing but “random paint strokes and splotches.” An iconic example of Pollock’s style is “One: Number 31.” While it appears to have a degree of improvisation to it, the work is purposeful in the sense that it is an attempt by Pollock to express the new concerns of his era in a new way. In 1950, he proclaimed “new arts need new techniques. The modern artist cannot express this age; the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture.” By eschewing the traditional style of past ages, Pollock effectively recreated the anxiety of living in the atomic era in a way that could be understood on a primal level. Pollock’s paintings also reveal another important aspect of modern art — it is not a medium that can be brought to you while being fully appreciated. I can listen to a song for instance on Spotify and get the same effect as listening to it on Apple Music because the art exists independently of physical space. Whereas paintings and visual art a lot of times are works that you have to go to due to the fact that they exist as objects in and of themselves.

Viewing Pollock’s work on your phone is not the same as actually going to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and actually viewing “One: Number 31” with your own eyes. In person, you can appreciate the subtleties of the color, strokes, texture and other aspects that are lost in digital translation.

Another example of modern arts unjustified infamy is the work of Mark Rothko. He is derided in a similar fashion as Pollock. I have heard his work described in person as “just red squares” or something that “anybody with a few buckets of paint could have done.” How is one supposed to find conceptual meaning in what amounts to a “color field?”

Well, according to Rothko, none. You’re not supposed to understand his work on an intellectual level. He was not seeking to represent events, places or even a subject. Rothko simply wanted you to sit down and observe his paintings and experience whatever feelings they gave. Doom, hope, ecstasy, tragedy. These are things that Rothko sought to elicit from his abstract expressionist works.

So while a 5-year-old might be able to paint a few squares on a canvas, they do not have the intention or deliberate action which Rothko utilizes. However, like Pollock, one can only really appreciate Rothko’s work in person. Through a screen, you are detached from paintings like “Red on Maroon” and are forced to view it in “stereopticon view.”

Even I find his work boring when looking at it through a picture. However, in person, his work becomes a humongous landscape. In person, you are “unable to command” the painting as Rothko would put it. When I went to the Tate Modern Art Museum, I stepped into the room and was forced to confront this work as an ominous and imposing object in and of itself. This is also why Rothko’s works are frameless and, in the case of the Tate Modern Art Museum, are in low lighting. Rothko describes his inspiration for this style in the Tate Modern by stating, “I was much influenced subconsciously by Michelangelo’s walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence. He achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after – he makes the viewers feel they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall.”

What each of these three iconic artists has in common is a willingness to experiment and reject tradition.

These traits are found in all the great artists in history; Monet, for instance, was rejecting the standards set by the Académie des Beaux-Art. His contemporaries most assuredly scoffed at his rebellious style.

But now Monet is hailed for his rebelliousness, while artists like Rothko are simply dismissed.

Why is that? One might say that modern art lacks skill and is commonly phrased as “I could do that.”

My response is simply “but you didn’t.”

While that seems flippant, it is a serious reminder that the artist chose how to execute every single aspect of their work, and to dismiss that fact is to forget how tough the creative process truly is, even if it is not physically difficult.

Another question is why does art need to be technically difficult to be considered art?

Again, if something can elicit emotional reaction so intense that it is felt for a century then surely one would call that artistic.

None of this is to say that no art is bad.

Not at all. There is modern art that I don’t like or I find uninteresting, and that is ok. You should examine art and find pieces that you don’t like. However, you should try to understand why you dislike the work instead of simply dismissing it all together as “not art.”

The question then is, how should one go about examining art?

Well, Backus has a pretty satisfying answer. In her TED Talk “Why You Don’t Get Contemporary Art,” she suggests you ask yourself four questions: What do I see/hear/smell/taste/touch? What are the materials? What do I feel? and What does this say about other art?

If you answer these questions, you too can begin to explore the world of modern art, and you might even find something cool along the way.

Vince Orozco is THE Managing Editor for “The Tiger Print.” Vince’s skills include rapping and writing long essays that nobody reads. In school, he...